SpyCloud researchers have obtained and analyzed a set of over 515,000 Telnet credentials and IP addresses associated with vulnerable hosts that were leaked on a popular criminal forum. The leak was first publicly disclosed by ZDNet in late January 2020, and efforts to contact affected ISPs and server owners are underway.

Backing up for a moment: It’s 2020, and people are still using Telnet. Yes, Telnet. We were surprised, too.

The risks of leaving Telnet ports open on IoT devices made security headlines back in 2016 when the Mirai botnet made a splash in the distributed denial of service (DDoS) scene. Mirai caused internet outages using a massive network of IoT devices that had been compromised via vulnerable Telnet ports. Given the widespread, high-profile damage inflicted by Mirai and the availability of secure alternatives, it’s surprising that IoT device manufacturers have continued to release products that use Telnet.

This dataset piqued our interest both because it involved Telnet and because it was compiled by a criminal rather than exposed in a breach from a legitimate source. Typically, our SpyCloud researchers recover data that criminals have stolen by breaching victim organizations. In those cases, we practice responsible disclosure and work closely with law enforcement to apprehend the responsible parties, which means we often can’t speak publicly about what we learn. In contrast, this data was collected by a threat actor for their own use and has been made widely available to both threat actors and researchers.

We were curious to see what we could learn about the compromised hosts that were included in the botlist. We hoped this dataset could help us understand whether exposed Telnet devices are still a problem, or if attackers are changing tactics. The results provide insight into how a botnet operator can grow their network of infected devices – and confirm that there are still plenty of exposed Telnet devices out there for attackers to exploit.

About the Telnet Data

The exposed dataset is referred to as a “botlist” because it was collected with the intent of infecting vulnerable devices with IoT malware, most likely a variant of Mirai. Often, the intention of this type of malware is to be used as infrastructure for DDoS-for-hire services called “stressers,” making distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks accessible to unskilled criminals. A DDoS attack overburdens a target network with excessive traffic, preventing legitimate users from accessing it. The more devices that are included in the botnet, the more powerful the service a threat actor can offer to clients–and there is no shortage of vulnerable systems available to use.

Here’s how this type of operation works: Attackers scan the internet for vulnerable devices to infect with IoT malware and attempt to log into those devices using common credential pairs, particularly the default logins set by manufacturers. Once a device is infected, it typically starts looking for other devices on the internet with exposed telnet ports or accounts to infect. In other words, the credential pairs within the botlist enable the malware to self-perpetuate.

Unlike combolists, botlists are rarely made public. A DDoS-for-hire provider can profit by using the botlist on their own than by selling or sharing the data. In this case, the threat actor who leaked this particular botlist claims to have moved on from using botnet-based infrastructure to cloud infrastructure. If this is true, it may be compromising cloud accounts and using the access to stand up infrastructure to use in attacks, or even maybe carding cloud services for such activity.

Our Analysis of the Botlist

After our researchers acquired the leaked botlist, we passively enriched the dataset to gain additional understanding of the compromised hosts, including GeoIP data, most affected networks, and a report on the highest ranking compromised usernames and passwords.

Once we deduplicated the dataset, we found that there were 201,302 unique credentials in the data, with 97,734 unique devices being infected.

We have redacted complete credentials to avoid providing potential access that could be used maliciously. We’ve also redacted “infections by network” to avoid revealing which networks would be most susceptible to attack.

Infections by Country

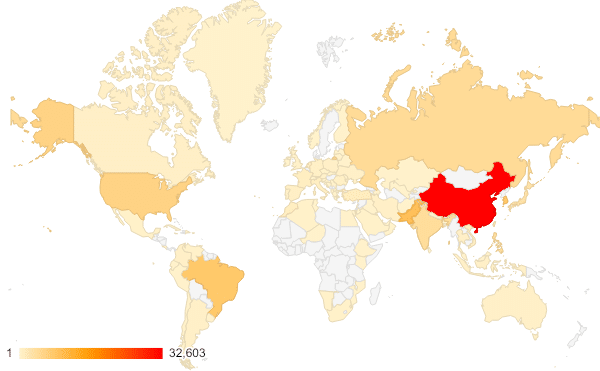

By enriching the leaked botlist with GeoIP data, we have been able to show which countries are most affected. As you can see in the map and chart below, the largest concentration of compromised devices in this dataset (33.9 percent) appears to be located in China. Pakistan comes in second with 9.7 percent of affected devices, followed by Korea (8.2 percent), Brazil (8.1 percent), and the United States (6.0 percent).

Examining the most prevalent usernames and passwords of exposed devices helps provide some clues as to why these countries have been hit hardest.

Heat Map: Infected Hosts by Country

Pie Chart: Infected Hosts by Country

Table: Top 20 Affected Countries

Infection Count | |

China | 32,603 |

Pakistan | 9,290 |

Korea | 7,873 |

Brazil | 7,751 |

United States | 5,770 |

Russia | 4,255 |

India | 3,905 |

Philippines | 3,657 |

Japan | 2,906 |

Taiwan | 1,946 |

Turkey | 1,107 |

Morocco | 952 |

Vietnam | 890 |

Netherlands | 850 |

France | 796 |

Italy | 736 |

Spain | 567 |

Hong Kong | 528 |

Canada | 515 |

Thailand | 474 |

Infections by Username

We have parsed the data to understand affected credentials by username, revealing that the vast majority of compromised accounts are users with special permissions. The top compromised username in the data was ‘root’, with ~57,811 infections (28.9 percent), and ‘admin’ ranks second with ~47,571 infections (23.7 percent).

These results are on par with what we would expect given that the type of malware infecting these hosts typically targets “super user” level accounts in order to run their malware on infected devices.

Pie Chart: Infected Hosts by Username

Infections by Password

The password ‘admin’ tops the list at the most compromised credential being used with ~42,870 infections (21.7 percent); ‘’ (no password required) ranks second with ~21,750 hosts infected (11.0 percent); and ‘root’ comes in third with ~20,203 hosts (10.2 percent).

Normally, this is where we would talk about the staggering rates of password reuse by individuals and how it enables criminals to take over consumer and employee accounts. (See our Annual Identity Exposure Report for an analysis of breach records we’ve collected over the last 12 months.)

However, this particular dataset tells a different story. The majority of the passwords within this botlist are associated with the default credentials set by device manufacturers, which would be publicly available in the device’s user manual. In many cases, device owners may not understand the importance of changing the default admin password, or that it’s possible to do so. Depending on the device, Telnet credential settings may not even be within the user’s control.

Some of these infections were found to be utilizing known manufacturer backdoors, such as the “default user” password of “OxhlwSG8” for Xiongmai video surveillance devices. Even if the device owner resets their admin password, this backdoor login remains active. Users are unable to take action unless the manufacturer provides a firmware update to patch the vulnerability.

Pie Chart: Infected Hosts by Password

Conclusion

Examining the botlist data provides insight into how botnets like Mirai can continue growing even if no new credentials are added to the list. Weak or default passwords and unpatched firmware make it easy for botnet malware to spread.

To protect your network from this type of malware, it’s important to know which devices are exposed to the internet, choose unique passwords, and keep track of firmware updates.

Suggested next step: Check your account takeover exposure. See results pulled from SpyCloud’s massive database of recovered stolen credentials.