Criminals Want Your Phone Number Almost As Much As They Want Your Password

In April, news broke that the personal data of more than 500 million Facebook users had been published to a hacking forum. Any leak of Facebook user data is newsworthy, especially one of that magnitude. What made this unique was that the data contained the mobile phone numbers that Facebook’s subscribers have linked to their accounts.

In the broader public conversation of identity theft, stolen phone numbers are often shrugged off. At the same time, any breach involving social security numbers or passwords sparks outrage – consumers feel violated by the criminals and betrayed by the service they entrusted with that data. Phone numbers are a different story. To consumers, the proliferation of telemarketing scams and robo calls proves that data is already in the wrong hands, so they shouldn’t be of much use to a criminal, right? But one need only to look at the SMS-based FluBot phishing campaign to see the ways these large troves of stolen digits can be leveraged for criminal activity.

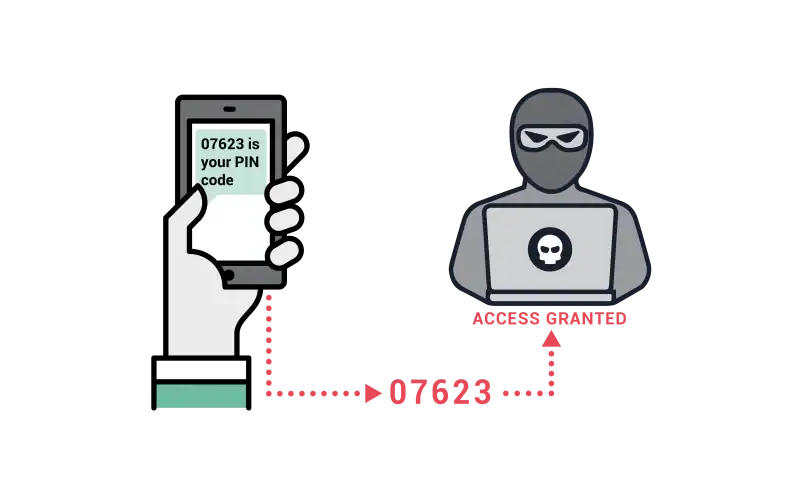

In recent years, as more digital services adopted multi-factor authentication (MFA), smartphones have become the primary touchpoint for businesses to confirm a user’s identity. The theory is that criminals might have a user’s password, but they probably don’t have their physical phone.

However, the right combination of stolen credentials allows criminals to bypass MFA using tactics such as SIM swapping and phone porting. With a simple call to a mobile carrier and some light social engineering, criminals can divert a consumer’s phone service to their own device. Once the attacker has control of the victim’s phone number, they receive all SMS-based authentication messages and can easily log into sensitive accounts (even corporate accounts) undetected.

For nearly every business or service a consumer engages with digitally – including the federal government – phone numbers are a primary identifier. Therefore, in fraud risk algorithms, organizations should be factoring in user phone numbers as primary identifiers of risk.

In the entirety of SpyCloud’s database, there are over 3 billion phone numbers that have been exposed in data breaches, including those from the Facebook breach. In fraud risk algorithms, organizations are used to checking usernames and email addresses for breach exposure, but adding phone numbers to that equation offers more robust insights than third-party identity authentication systems can provide.

Even if you have already authenticated a user by other means, the ability to check that user’s phone number against SpyCloud’s database can reveal additional exposures that could help determine whether to delay or block a possible fraudulent transaction. It is very possible that a bad actor has taken over a user’s account or even fooled biometric validation systems.

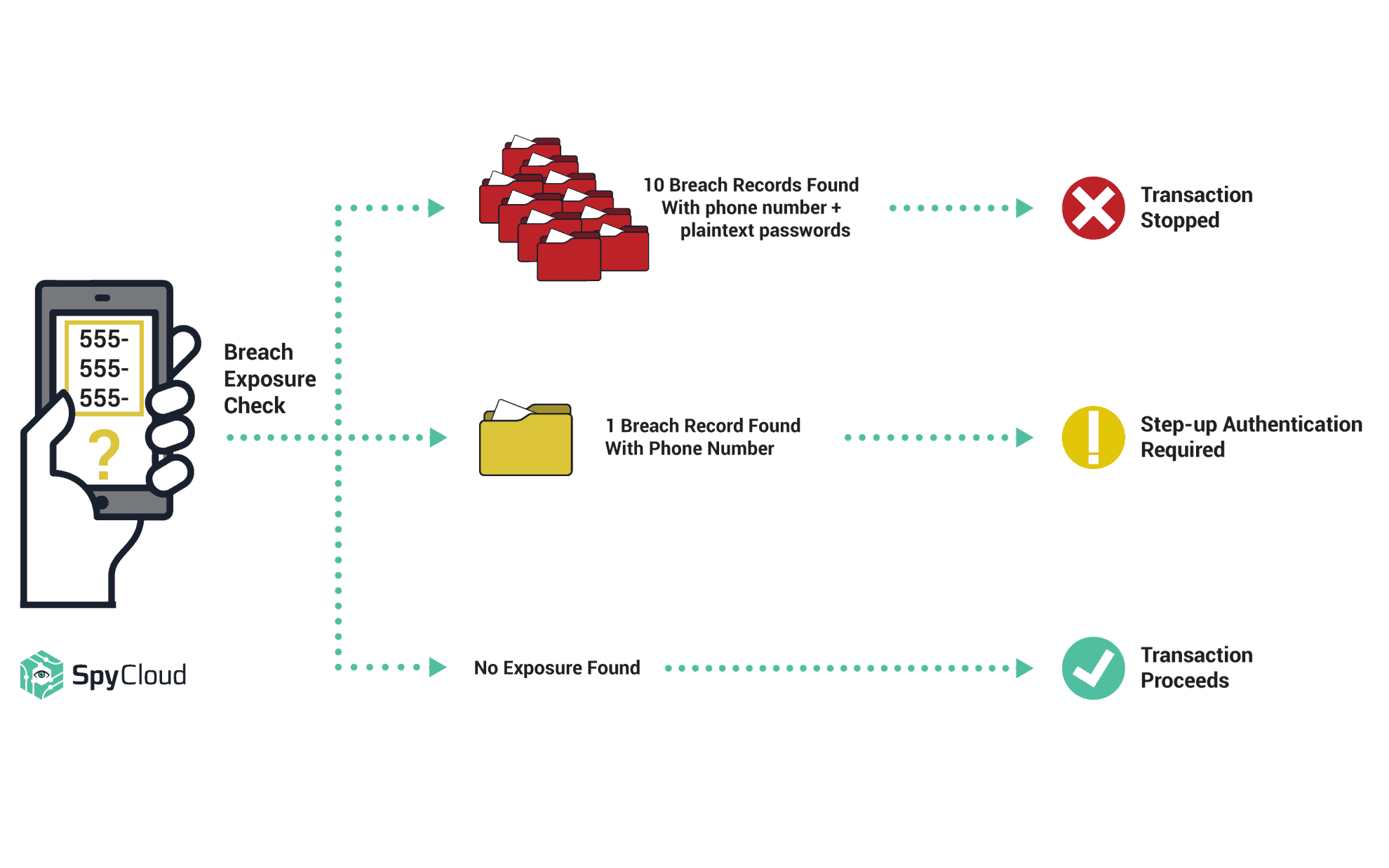

In the example illustrated below, a user’s phone number is checked for the number of times it has been exposed in data breaches:

For some SpyCloud customers, just 1 appearance of a subscriber’s phone number in a breach record means that person will go through another form of step-up authentication before the transaction will be approved. Ultimately, each company’s risk tolerance will vary.

Digital services have been requiring mobile phone numbers for access for years and it’s unlikely to stop. Furthermore, unlike credit card fraud, for example, it’s far more inconvenient to issue user’s new phone numbers every time they are compromised. As SIM swap attacks continue to rise, adding phone numbers to your fraud algorithms can not only help identify potentially compromised users, but also curb the financial risk to your organization.