During the Summer of 2022, a Chinese data breach was posted for sale on the English-language cybercriminal forum BreachForums and immediately made international headlines. The Shanghai National Police (SHGA) database breach was particularly notable for two reasons:

- Its origin: It was one of the first large Chinese data breaches that made waves in Western cybercrime and cybersecurity research circles.

- Its sheer size: If the description of the seller ‘ChinaDan’ could be believed, the data breach contained PII on a billion Chinese residents, including names, addresses, phone numbers, national ID numbers, and in some cases criminal record information.

At the time, the dataset was being offered for exclusive sale at a high price (10 BTC),[1] but large datasets that are sold exclusively often continue to propagate online and are eventually re-leaked. In February 2025, SpyCloud obtained a re-circulated copy of a dataset that appears to match the ‘citizens database’ from this 2022 breach. This database contains 960 million rows of names and national ID numbers for Chinese citizens, as well as some additional PII for a subset of those citizens.

Our team took the rare opportunity to analyze such a large dataset of Chinese national ID numbers, which, as we will discuss, each inherently contain additional data points embedded within them.

Some background on national ID numbers

Different governments have their own systems of assigning identification numbers for citizens. Because these numbers are usually centrally assigned by national government authorities, they act as convenient identifiers to track individuals because they are unique, consistently formatted, and often follow people throughout their lives. In a way, national ID numbers are kind of the ultimate JOIN values. As a result, they often get used beyond their originally intended purpose and by other entities besides just the government.

If you’re in the US, think about the last time you underwent a background check for an apartment, job, or line of credit – they probably asked for your social security number (SSN) despite having no association with the Social Security Administration or the US government. That’s because your SSN is used to track you as a unique individual across a variety of third-party databases that have nothing to do with social security.

Often, different national ID-issuing authorities assign these numbers according to systems that embed additional data about an individual within the ID number. In the US, SSNs assigned before 2011 contain a 3-digit area number that corresponds to the geographic region where the SSN was assigned. Other national ID numbers have significantly more embedded data, including birthdates, geographic information, legal status information, and gender.

Chinese citizenship ID numbers

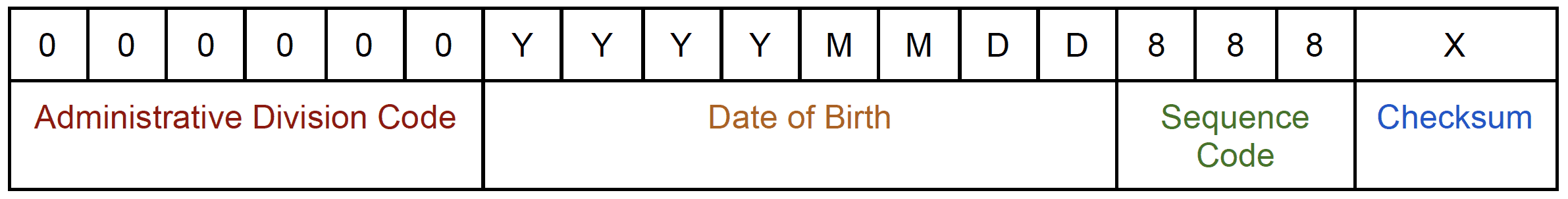

The Chinese citizenship identification number (公民身份号码) serves as their national ID number and contains quite a bit of embedded data. These numbers are 18-digits long and follow the following format:

Administrative Division Code: This 6-digit number corresponds to the geographic location where the ID number was assigned; often the individual’s birthplace. The first two digits correspond to the province, the second two to the prefecture, and the last two to the county or city.

Date of Birth: The next 8 digits correspond to the individual’s date of birth according to the Gregorian (Western) calendar in the YYYY-MM-DD format.

Sequence Code: The next 3 digits are referred to as the “sequence code” and are used to differentiate between people with the same birthplace and birthdate so that each person has a unique ID. It also corresponds to the individual’s gender: odd sequence codes are reserved for males and even sequence codes are reserved for females.

Checksum: The final digit is a checksum calculated from the other digits in the ID. To keep the number of digits consistent, a checksum value of 10 is represented by the letter X, so sometimes this final character might be an ‘X’ instead of a numeric character.

These numbers are also even more frequently collected by Chinese digital apps and services than might be the case in other countries. China has a “real-name system” in which the government requires digital service providers to collect users’ real identity information before providing access or services. This leads to many apps requiring users to give them lots of personal information before they are able to make an account and use the service, including in many cases their 18-digit citizenship ID number.

Connecting the dots between ID numbers and leaked data

Like mobile numbers, Chinese citizenship ID numbers can serve as extremely useful pivots to link an individual’s information between breached and leaked datasets. As we wrote about last fall, Chinese criminal social engineering databases (written as 社工库 in Mandarin or abbreviated as SGK) almost all use mobile number and national ID number as data types that can be used to query breached and leaked PII on individuals. SGKs serve as repositories of leaked PII; they are created by Chinese-language threat actors who compile hacked and leaked databases together allowing other criminals to easily find accurate personal information on anyone.

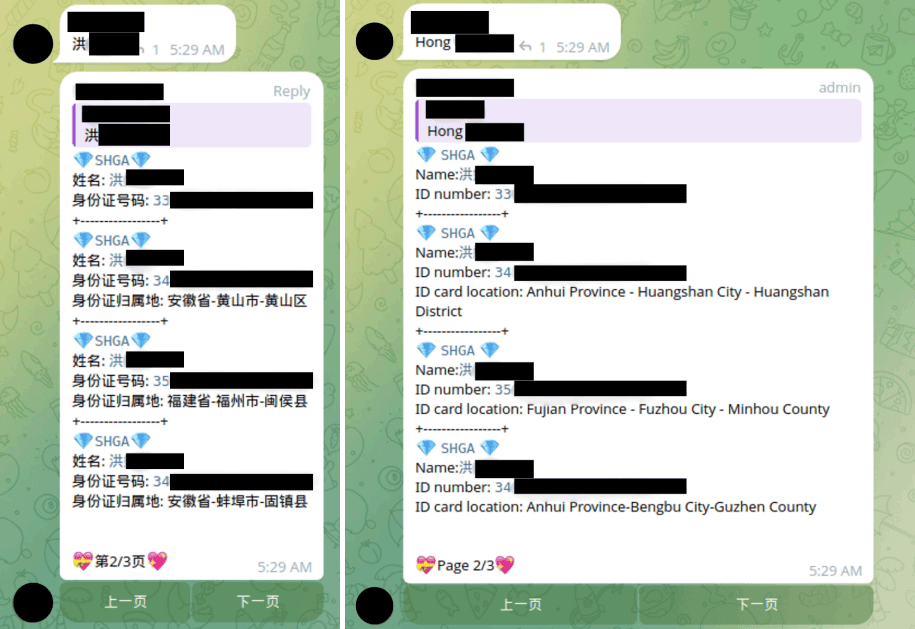

In the screenshots below, you can see an example of an SGK bot query and associated results which contain data that appears to have come from the SHGA breach. In the messages, a user queries the SGK bot for someone’s full name. Then, the bot responds with multiple results, all of which appear to come from the SHGA data breach as a source. Each result contains a distinct ID number associated with that full name, likely from multiple distinct individuals who share the same name.

Additionally, most of the results also include an “ID card location” which appears to have been derived by the SGK bot administrators from the 6-digit administrative division code in each ID number. Threat actors who obtain leaked Chinese national ID numbers can easily extrapolate additional identity data about an individual, including their birthplace, birthdate, and gender.

Screenshots from an SGK bot on Telegram. On the left are the messages in Chinese, and on the right are English translations.

Crunching the numbers from the Shanghai National Police database breach

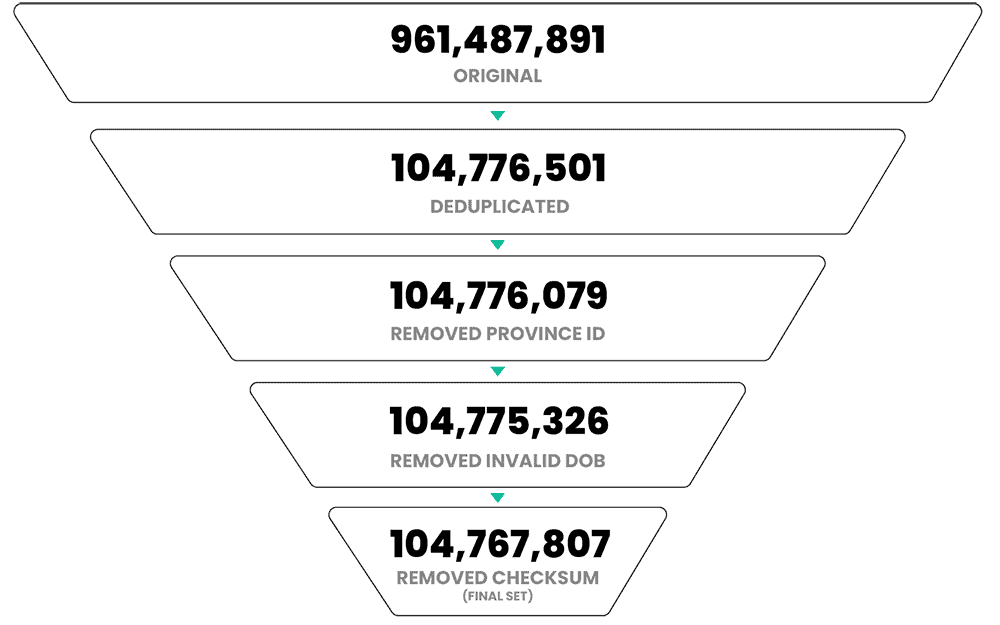

Before we were able to create meaningful statistics with the ID numbers in this breach, we actually had to clean up the data quite a bit. Taking just the ID numbers from the Shanghai National Police database, we first deduplicated the national ID numbers as whole integers. This first step significantly reduced the amount of national IDs, taking it from 961,487,891 (almost 1 billion) records down about ten-fold to 104,776,501 unique national ID values.

Next, we looked at the administrative division codes. The most recent authoritative listing of valid administrative division codes that we could find was published in September 2015, so we didn’t feel confident invalidating all of the six-digit codes that didn’t match this list because new divisions could be added. However, we thought that the province codes (the first two digits) were less likely to change significantly over time. We found just over 400 ID numbers with invalid province codes, leaving us with 104,776,079 remaining unique national IDs.

Next, we checked for invalid dates of birth. This step was pretty straightforward, we just checked for any remaining national IDs with impossible birthdates like May 45, 1997 or December 28, 2045. We removed 753 more national IDs, leaving us with 104,775,326.

Finally, we used the checksum equation to invalidate national ID numbers according to the ISO 7064:1983, MOD 11-2 checksum algorithm. This method serves as an efficient way to detect single substitution errors and single transposition errors, common mistakes that occur with manual data entry.

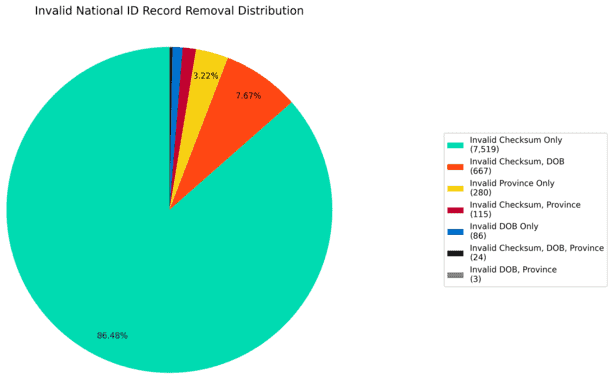

After this step, we removed 7,519 more national IDs, leaving us with a final count of 104,767,807 unique, valid national ID numbers. Without access to Chinese government databases, we can’t say with complete certainty that all of the remaining ID numbers (and associated data) are accurate or valid. But, based on these validity checks, we can say that only 0.008% of the unique ID numbers appear to have any clear issues that would render them obviously invalid.

Pie chart showing the different reasons that national ID numbers were invalidated and removed from our dataset, including national ID numbers that failed multiple validation checks.

Visualizing the national ID data

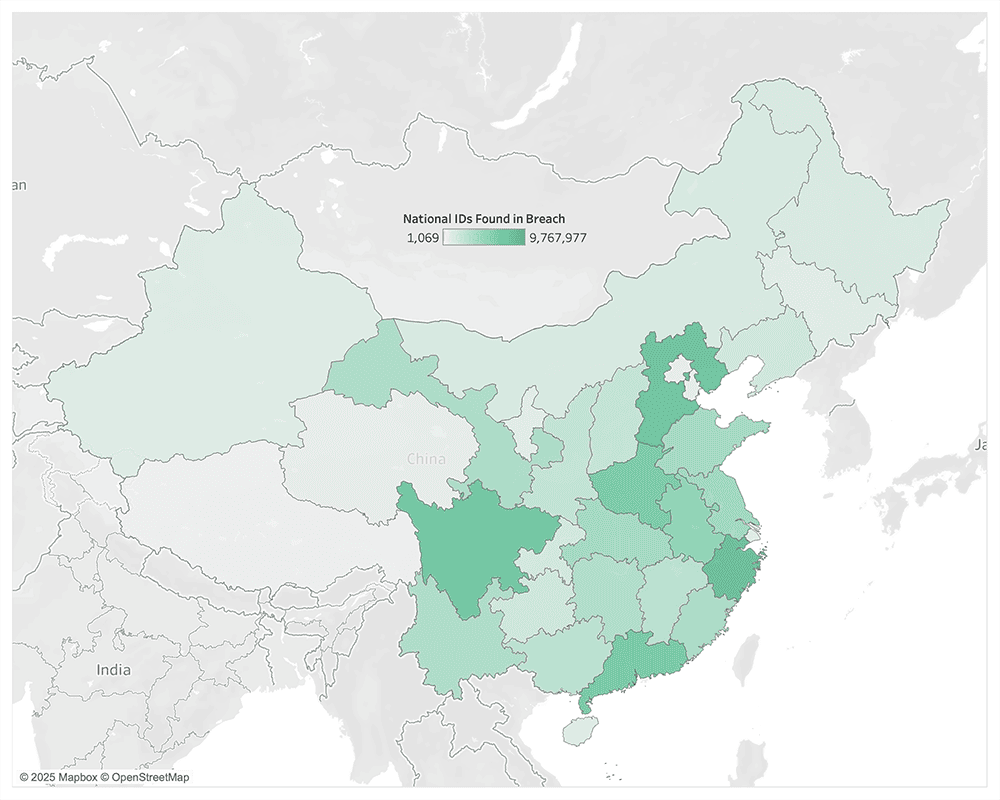

Finally, we were able to make some visualizations using the data that we derived from this set of national IDs to provide more interesting views of the millions of individuals whose data was exposed in this breach. By deriving data from the national ID numbers, we were able to obtain a location, date of birth, and gender for each of the individuals, allowing us to create data visualizations with the extrapolated data.

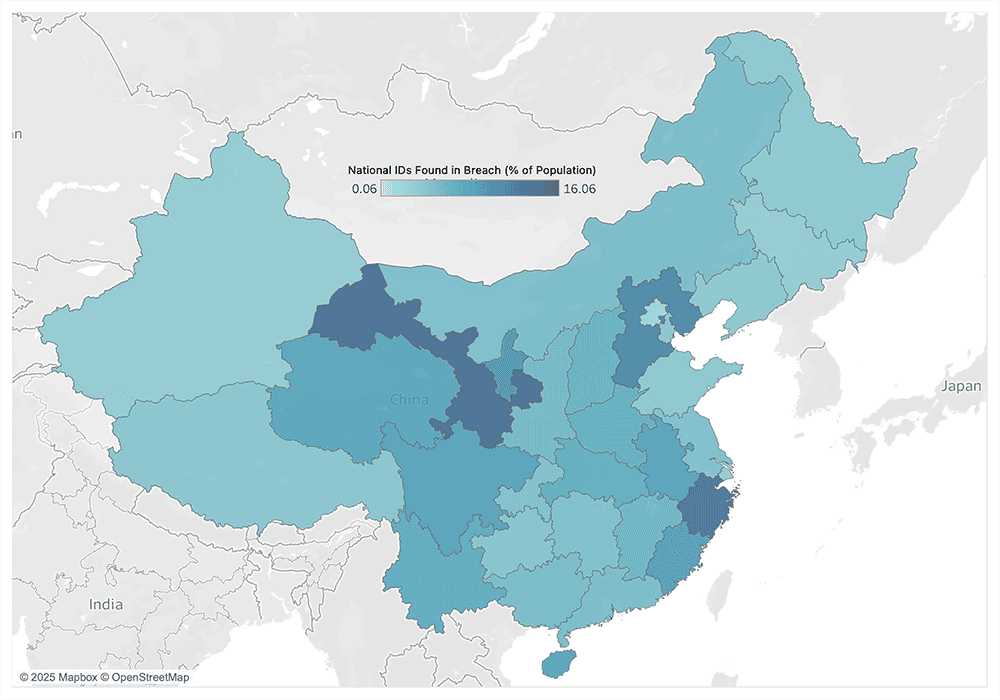

First, we made two choropleth maps to visualize where the Chinese citizens in the database were born. We created two maps; the first shows the concentration of where individuals’ in this data were from as simple totals. The second also shows concentrations of where people are from, but this time as a percentage of the total population of each province.

Choropleth map showing the distribution of the number of valid deduplicated national ID numbers in the dataset originating from each province.

Choropleth map showing the distribution of valid deduplicated national ID numbers in the dataset originating from each province as a percentage of that province’s total population in the year 2022.

As you can see in the table below, only two provinces, Zhejiang and Hebei, ranked in the top five across both of these measurements. Zhejiang shares a border with Shanghai. Gansu, a Chinese province with an arid climate and high levels of poverty, ranks eleventh on the list of total individuals in the SHGA database, but first as a percentage of the population. This may be an indication that a lot of people from Gansu emigrate to other areas of China for economic opportunities. Shanghai, as the largest city in China, has a lot of immigration from more rural areas.

| Top 5 Provinces (Totals) | Top 5 Provinces (% of provincial population) | ||

| Zhejiang | 9767977 | Gansu | 16.06% |

| Hebei | 9372810 | Zhejiang | 14.85% |

| Sichuan | 8153000 | Hebei | 12.63% |

| Guangdong | 7659325 | Ningxia | 11.05% |

| Henan | 7542219 | Fujian | 10.07% |

Table view of the top five birthplaces represented in the breach, and of the top five birthplaces by percentage of the that province’s total population.

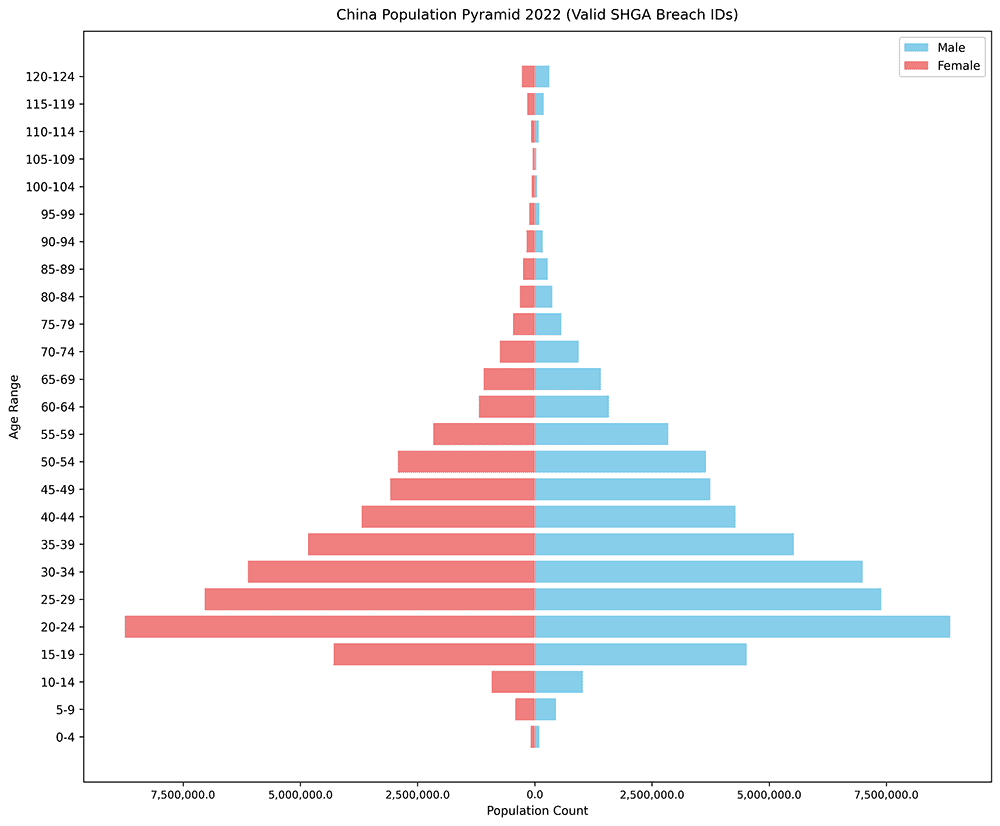

Next, we looked at birthdate and gender. We created a population pyramid showing the distribution of individuals in the dataset by gender and age bracket. As you can see below, the population pyramid for the SHGA data skews heavily towards younger adults, with the 20-24 age range as the highest by far, accounting for 16.8% of all of the individuals in this breach.

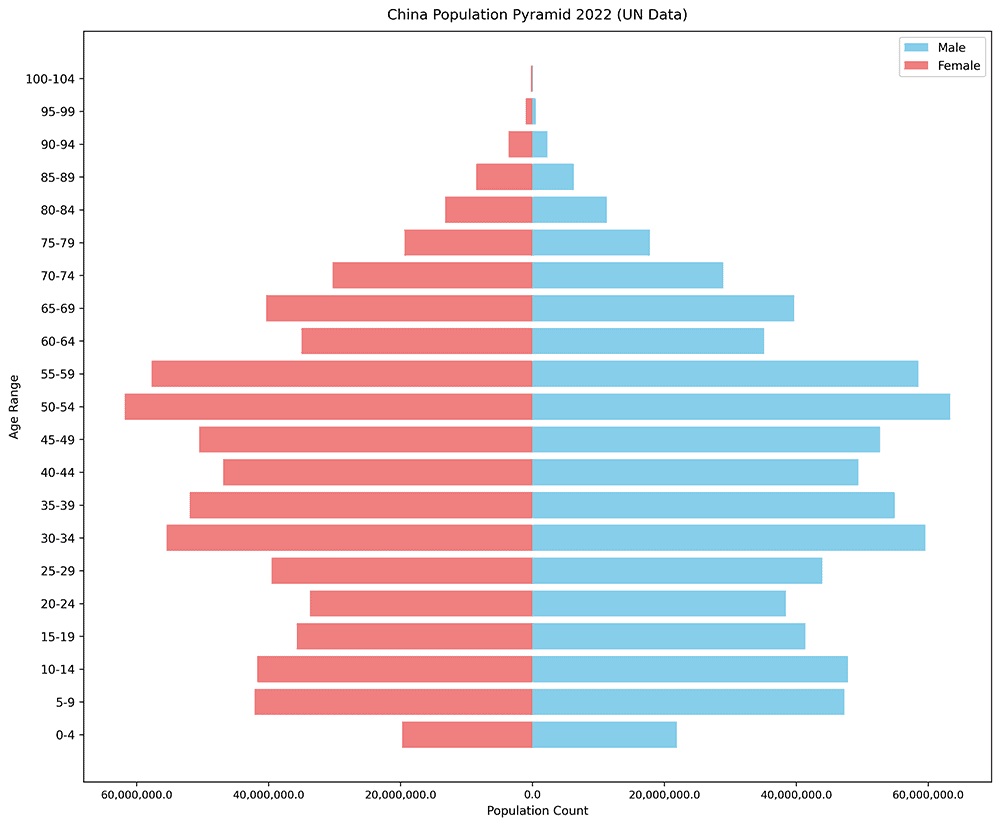

We also created a population pyramid from UN data about the entire population of China to visually compare the two; the pyramid visualizing the UN data has a much more consistent distribution of individuals in each age bracket.

The skew towards younger adults in the SHGA data may be a result of the progressive digitization of government records over time, causing this source to have a higher concentration of digital data for younger adult citizens than older adult citizens.

Additionally, the SHGA data contains data on individuals over the age of 104, which is not reflected in the general population data. This indicates that data on individuals is not purged from this SHGA database after their death.

Population pyramid showing the distribution of age and gender derived from national IDs in the SHGA data breach.

Population pyramid showing the distribution of age and gender for the total population of China.[2]

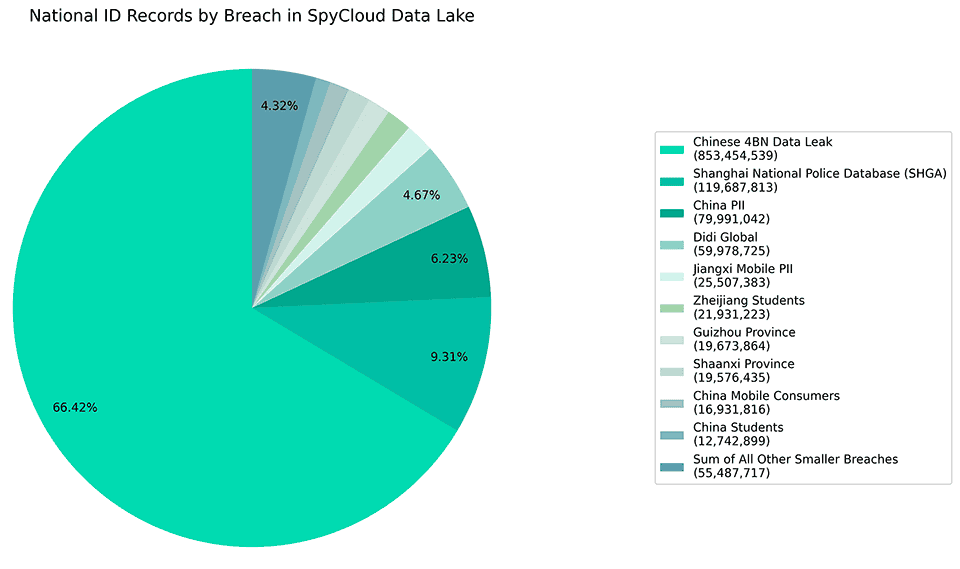

We also analyzed how this collection of national ID numbers stacks up against other breaches with data on Chinese citizens, as well as against China’s overall population, and found that:

- The SHGA breach contains the most Chinese national IDs of any single-source breach SpyCloud has ever collected, amounting to nearly a tenth of the Chinese national IDs in our data lake. The only breach we have collected that contains more Chinese national ID numbers was the headline-grabbing 4 billion record data leak from June of this year, which based on our analysis was actually compiled from a variety of different sources.

- This breach contains national ID numbers for approximately 7.4% of China’s total population.

- This breach contains national ID numbers for more than four times the current total number of residents of Shanghai.

Pie chart breaking down the percentage of national IDs from different breaches in SpyCloud’s data lake of breached and leaked data.

Key takeaways from our analysis of the Shanghai National Police database breach

The SHGA database breach was a very significant breach that exposed the PII of millions of Chinese people. Notably, the breached data contains over 100 million unique Chinese national ID numbers, making it similarly impactful to recent large breaches of US persons containing SSNs including the National Public Data (NPD) breach and the MC2 data breach.

Chinese national ID numbers, like lots of other national ID numbers around the world, contain a ton of embedded data. Because of this, threat actors who obtain the leaked data can extrapolate and potentially abuse additional identity data about a given individual, such as birthplace, birthdate, and gender.

Even though the SHGA breach is very large, it definitely doesn’t make up a representative sample of all Chinese people based on our analysis of data derived from the ID numbers from the breach. Instead it has geographic, age, and gender biases that don’t match China’s overall population. We attribute some of these biases to immigration patterns within China as well as to the incompleteness of government record digitization.

For more on the Chinese cybercrime ecosystem, see other recent research from SpyCloud Labs.

[1] Approximately $350,000 USD at the time.

[2] Note: This data was collected in 2020, and we are extrapolating to fit individuals’ ages in 2022, so there are no individuals under the age of 2 represented in the data.