For years, the majority of industry security research and public reporting has focused on cybercriminals based in Western countries and Russia. While there’s cause for this – many sophisticated cyberattacks and subsequent data leaks have been attributed to cybercriminal groups based in those regions – as a research community, we’re missing a growing piece of the puzzle lurking right under our noses: the Chinese-language threat actor community.

On Telegram, X (formerly Twitter), other social media sites, and underground forums, Chinese hackers, data brokers, crawlers, and salesmen have built a vast ecosystem of illegal data trade advertising large amounts of personally identifiable information (PII) data. Through SpyCloud Labs research, we’ve found that this data is being procured through traditional means as well as through tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that have been crafted to fit the unique landscape of China’s telecommunications industry:

- Traditional TTPs for data exfiltration include vulnerability exploitation and SMS-based attacks

- Unique TTPs for data exfiltration include malicious software development kits (SDKs), deep packet inspection (DPI), penetration services, insider access underpinned by formal contracts, and counterfeit mobile applications

- Traditional TTPs for data exfiltration include vulnerability exploitation and SMS-based attacks

- Unique TTPs for data exfiltration include malicious software development kits (SDKs), deep packet inspection (DPI), penetration services, insider access underpinned by formal contracts, and counterfeit mobile applications

In this blog, we’ll break down our findings, which underscore Chinese-language actors’ ability to consistently leak and disseminate large amounts of data.

Why it matters: Impact of Chinese threat actors

This illegal trade network impacts both Chinese entities in addition to global organizations, as Chinese-language cybercriminals increasingly target international people and businesses. Based on various, though unsubstantiated by SpyCloud Labs, reporting by Chinese media outlets in early 2022, the value of the black data market has been estimated to be between 100 – 150 billion yuan[1].This figure is based on estimates shared by alleged industry experts who spoke directly to the media. In January 2024, one Chinese news outlet claimed that this figure actually surpassed 150 billion yuan[2].SpyCloud Labs has not been able to locate the original sources of these estimates.

It is important for us as a community to understand the difference between data leaks published only on Western channels, data leaks published on Chinese channels, and data leaks published on both as the threat of Chinese actors’ cyber-capabilities continues to grow. Research only focused on Western channels misses a substantial basis of information unique to Chinese-language actor communities and is rarely transported across linguistically-defined boundaries.

Research findings: Trends and TTPs

Telegram has enabled China-based actors to circumvent surveillance that they could normally be subjected to within their country. These actors use proxy or VPN services to connect to the messaging app. Analysts at SpyCloud Labs have observed the use of the following trends and TTPs by Chinese-language threat actors on Telegram.

Telegram advertisements and keywords

Chinese-language Telegram actors leverage their own vernacular to describe and advertise their stolen data. This vernacular is made up of Chinese colloquialisms and keywords used to convey specific data types, targets, victims, and job functions of individuals involved in illegal data trade.

| Slang Term | Chinese Characters | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Pantsless data, Trouser removal data, Take off pants data | 脱裤数据 |

Term meaning to hack the data of all the users of a website. Learn more |

| Spinach | 菠菜数据 | Term used for online gambling/casino/chess industry data |

| Industry-wide data | 全行业数据 | Term used for domestic data leaks |

| Red hat hacker | 红帽黑客 | Term used for hackers loyal to the PRC |

| Selling dog meat by hanging a sheep’s head | 挂羊头卖狗肉 | Term used for deceptive data brokers selling second-hand, low quality data |

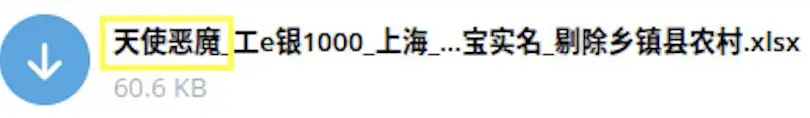

| Angels and demons | 天使与魔鬼 | Used to describe Public Security Bureau/police or internal bank employees |

A sample file using the keywords “Angels and Demons” to refer to this financial-related database.

SpyCloud Labs has observed that these data leak advertisements largely follow a specific structure that obfuscates certain details, such as victim name, which is likely a measure to maintain access to that entity in addition to protecting their data from law enforcement intervention. Instead of revealing a specific company name, these actors will often refer to their breached data by using keywords affiliated with the sector the victim entities inhabit.

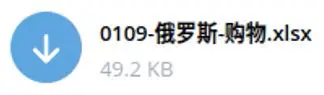

A sample file including the personally identifiable information (PII) of Russian citizens translates to “Russian Shopping Data” and was available for download on a Chinese Telegram channel.

This word cloud illustrates the most common keywords used in Telegram mentions of DPI and SDK data. Translated phrases include “high quality”, “accurate data”, “overseas”, “industry”, and “first-hand.”

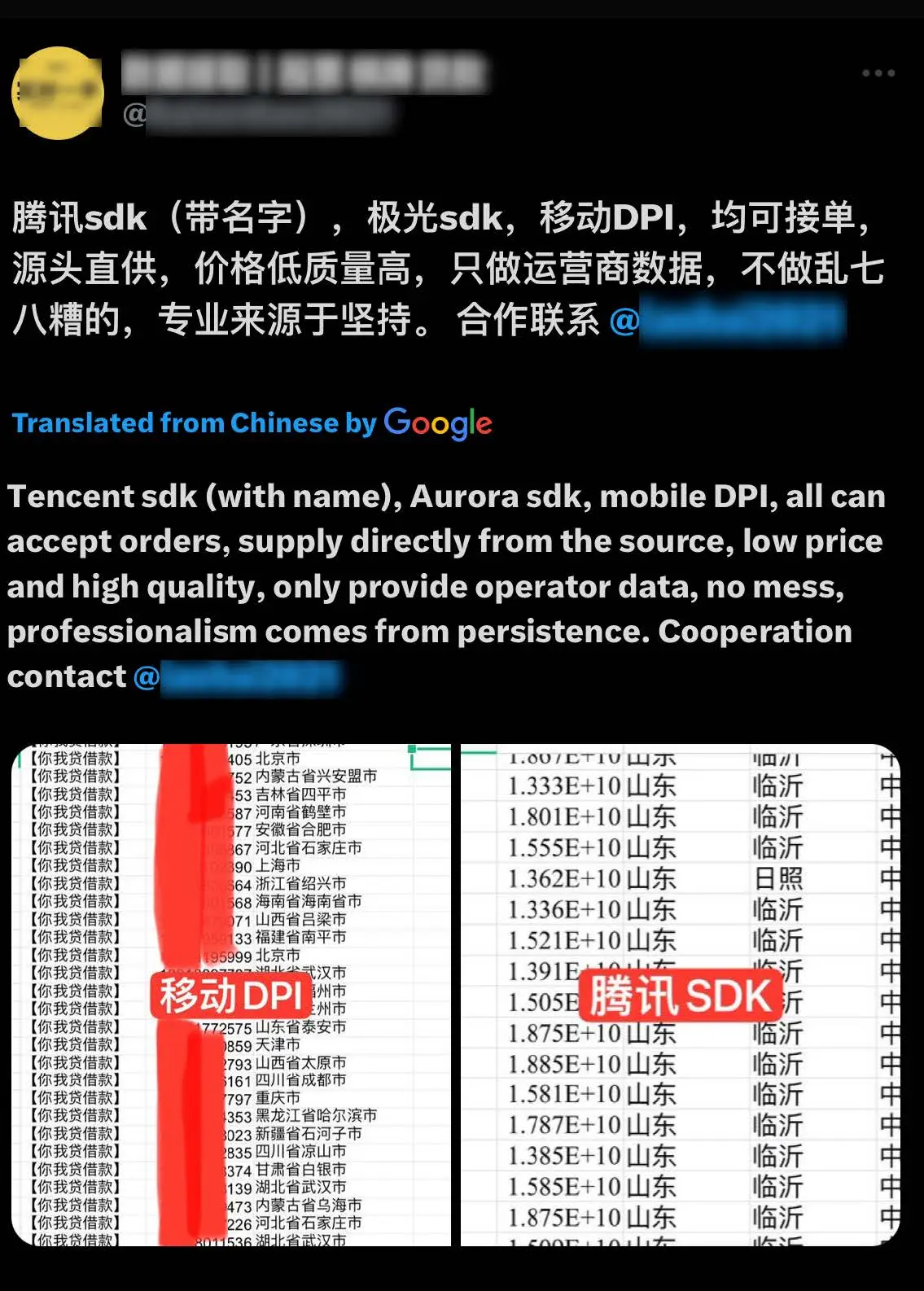

X (Twitter)

Data exfiltration methods

Data disseminated by Chinese Telegram actors is often referred to by its value, relative to the method used to exfiltrate it. “High value” data is perceived by these actors to be both accurate and timely – so timely in fact, that data is sometimes referred to as being breached in near “real time.”

- Accuracy: Login Access > SMS > DPI > SDK > Penetration Tools (Crawler/Reptile)

- Timeliness: Login Access > DPI > SMS > SDK > Penetration Tools (Crawler/Reptile)

When these actors receive data requests from potential or existing customers, they will attempt to acquire the data through the most timely and accurate collection and exfiltration methods first. If the requested data cannot be collected through login access, the actor may choose to attempt to acquire the data through SMS or DPI methods, and so on.

Login access

According to members of the Chinese-language threat actor community, the most accurate and timely data is collected via direct “login access.” Sellers will claim they have login access to apps or websites which they can easily exploit, making them the only person involved in the data exfiltration and subsequent data selling.

Unlike the methods that will be subsequently addressed in this blog, data exfiltrated directly from its source does not have to change hands between the source to an insider, middle-man, or data broker before it reaches the customer. This enables actors to exfiltrate data with more confidence and control of its fidelity and timeliness. Actors will claim to have backend permissions to these resources, most likely maliciously acquired.

Actors are well-versed in the vulnerabilities of certain apps, and SpyCloud Labs researchers have observed these actors primarily advertising backend access to specific industries including lottery, sports, chess, and casinos.

This data can include both domestic and foreign PII.

SMS hijacking, smishing, pseudo base stations

China-based Telegram actors consider data collected through various SMS-focused attacks to be the second-most accurate type. This is in part due to the limited interference required in order to intercept and exfiltrate sensitive information. In the case of man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks, reply attacks, and SMS sniffing, an unauthorized third party intercepts information shared between an end user and a trusted party and uses social engineering techniques to collect sensitive information. Actors will use message templates with keywords that are known to be used by major entities, like banks, to trick their victims into trusting that the messages that they are receiving are legitimate.

Pseudo base stations (PBS), which are malicious types of mini cellular towers, can be used to steal personal information from nearby mobile devices through SMS sniffing. PBSs intercept the legitimate GSM signals transmitted between mobile devices and telecommunications networks. Two of China’s three major telecommunications companies (China Mobile and China Unicom) use GSM. Therefore, there could be up to hundreds of millions of Chinese mobile phone users on GSM-enabled networks,[3] and a number of citizens in China are also subjected to data theft from vulnerabilities in the GSM protocol.

GSM networks can also be maliciously used to infect mobile devices to ostensibly access and exfiltrate sensitive data, though at this time, researchers have not confirmed whether this is a common tactic used by Chinese Telegram actors.

This data may be perceived as less timely, compared to its accuracy, likely due to the length of the attack cycle. Leveraging social engineering tactics to collect sensitive data generally takes longer to aggregate once collected.

Data collected through SMS interception can include phone numbers, telecom providers, verification codes, and location information.

Deep packet inspection (DPI)

Telecommunications providers, like those mentioned above, use deep packet inspection (DPI) for managing traffic within their respective networks. DPI inspects network frames at a more holistic and invasive level, often through SSL cracking/decryption, in order to correctly classify traffic. Because of this decryption, sensitive information is subject to exposure if the DPI analysis lands in the wrong hands.

Telegram actors advertise “DPI” data, which often includes PII like phone numbers, location information, IP addresses, and URLs. These actors ostensibly are able to access this data through signed formal agreements with China Telecom, China Unicom, and China Mobile. This signals a willingness of presumably legitimate employees to foster illicit relationships with Telegram-based actors who sell and share this data in their respective channels. It is unclear whether telecommunication employees benefit financially or otherwise from this partnership, as specific examples of these formal agreements have not been publicized.

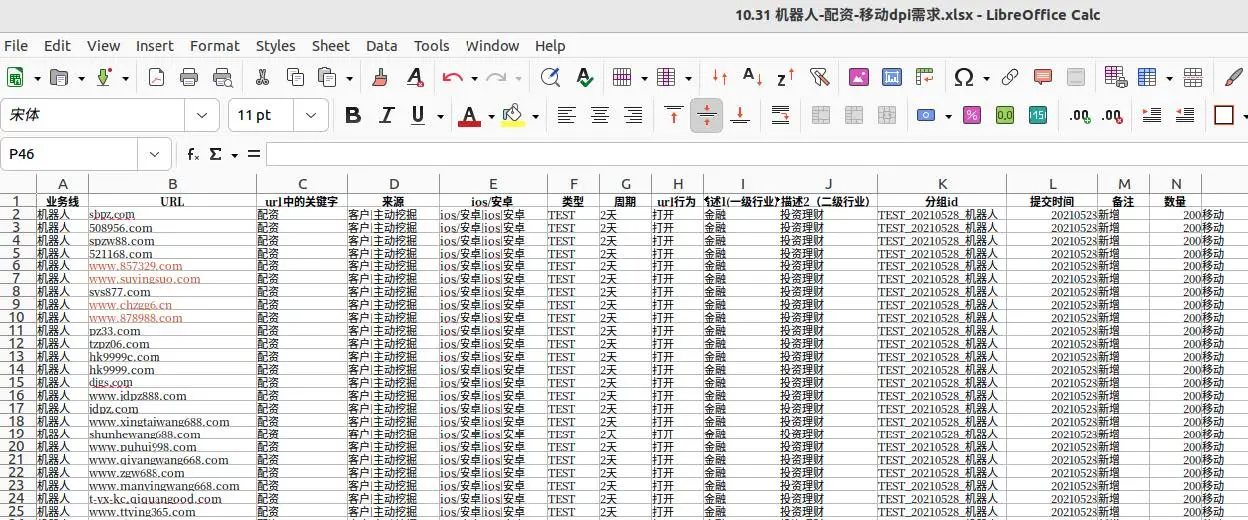

A sample of DPI data shared by a Telegram-based actor. This file is called “Robot Finance Allocation Mobile”, possibly indicating that this data originated from financial-adjacent companies.

DPI tends to primarily be made up of domestic data, though tourists and foreigners can be subjected to data theft via DPI. One way this can happen is if a non-China resident visits the country and purchases a Chinese SIM card in order to have persistent network access. When the phone attempts to communicate over the network, that traffic is subjected to DPI.

On the accuracy scale, DPI falls squarely in the middle. This may be because DPI data – while it is made accessible through insider access – is still originating from a source that is not owned by the threat actor selling it. It is considered to be the second most timely data exfiltration method, which may be attributable to data turnaround times possibly expressed within the signed formal agreements.

Software development kits (SDK)

Software development kits (SDKs) are legitimate packages of software tools that are bundled together to be used by app developers. SDKs are often built separately from the applications themselves, leaving room for malicious actors to produce their own SDKs to shop around to developers. In some instances, this includes acquiring SDKs from open sources like GitHub, where over 8,600 public SDK repositories are currently hosted. Depending on how an SDK is configured and how it is later used by developers to encode capabilities within their app, varying types of personal and sensitive data can be collected and exfiltrated. This information may include phone numbers, genders, ages, and location information. Most SDK data tends to be domestic PII of Chinese citizens.

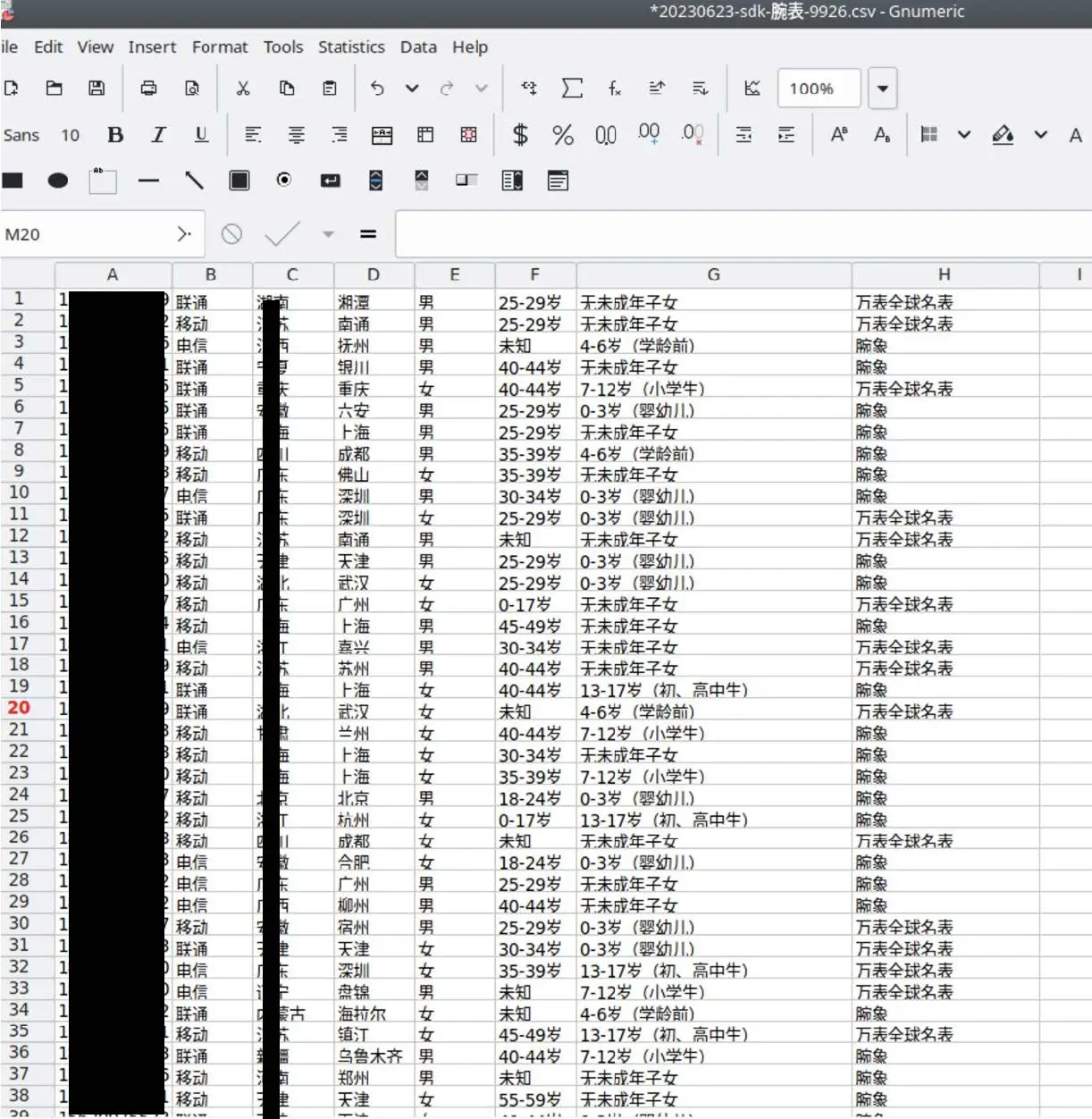

A sample of SDK data shared by a Telegram-based actor. This file is called “sdk watch”, which may indicate that this data belongs to retail consumers. This data includes phone numbers, names, ages, and other information.

Some Chinese-language actors claim to have relationships with mobile phone manufacturers, suggesting that they have been given backend access to the SDKs of apps natively a part of a mobile phone’s operating system. The exact nature of this type of relationship is unclear, and it is unknown if signed formal agreements are used, like with DPI data brokers.

The majority of actors advertising SDK data are likely further removed from the data source than those who claim to have backend access. Actors have been observed advertising their SDK data with “t+1” and “t+2” attributes. These attributes likely are referential to the amount of time in days after the initial leak date (t) that buyer will receive their order. These one- and two-day windows ostensibly give the seller enough time to procure the data from their contacts to deliver to the end customer.

In English-language and other ostensibly Western Telegram channels, malicious SDKs are advertised under the guise of “affiliate marketing” campaigns, where actors financially incentivize potential users of their SDKs with ad revenue. It is unclear whether China-based actors attempt to incentivize developers to use their malicious SDKs in the same way, as there is less public discourse regarding the advertising of their SDKs. The lack of public discourse may suggest that these discussions are happening in closed communities in order to protect their access.

SDK is considered one of the least accurate and least timely exfiltration methods. Security-minded individuals may opt to limit the amount of personal information they share with an application or may knowingly submit incorrect information in order to best protect their identity, therefore marring the fidelity of the exfiltrated information. It appears that many SDK sellers on Telegram are several steps removed from the SDK data source, meaning this information has to pass through several hands before getting to the customer, further diluting its timeliness and accuracy.

Penetration tools

Chinese Telegram actors have been observed relying on third party entities to support their data trade. This can include known penetration tools like web crawlers, fraudulent (trojanized) mobile applications, and phishing kits. These methods are employed to target overseas data and in cases where actors do not have insider or direct SDK or DPI access. SpyCloud Labs analysts have observed these penetration services being offered for between US$12,000 and US$14,000.

Other facets of the illicit data trade ecosystem

CVV/POS financial data

Chinese data sellers turn their attention to global victims to supplement their financial data offerings. This is in part due to the popularity of mobile payments – as opposed to direct credit card transactions – in China through apps like AliPay and WeChat. Based on public chatter within these channels, it appears that many actors leverage both credit card sniffing and phishing kits to target their victims and exfiltrate financial data. The specific tools and methods are only shared privately.

Though data sellers often advertise credit cards from a variety of countries, many advertisements explicitly highlight the availability of US- and Japan-based credit card data, likely due to the high per capita wealth in both countries. Telegram channels advertising credit card information will commonly use English-language keywords like “CVV” or “CVV/POS” to refer to their credit card offerings, likely to denote that they have complete sets of credit card numbers, including CVV codes.

Operators of these Telegram channels sometimes leak entire sets of credit card “fullz” either directly in a channel message, or as a text file, most likely as a proof of concept. Credit cards that have been checked, or have had a small pre-authorization charge run against it, will cost more than cards that have not been validated.

Social Work Libraries (SGK)

Chinese threat actors create their own centralized repositories of leaked PII into what is referred to as Social Work Libraries (SGK.) It appears that once an actor sells a dataset, they will wait a certain amount of time, and then upload that sold data into their SGK. These libraries often require users to register with an email address or username and password, though it appears that there are no overt restrictions to who can register. Registered users can search through the structured dataset for various records including QQ IDs, passwords, email addresses, and phone numbers. Most SGK’s offer tiered access, with “free users” (users who have registered, but have not deposited any BTC to their account), being able to run search queries, but get only limited and obfuscated results, with more complete results existing behind a paywall. SpyCloud analysts have limited the scope of their current research to unpaid library tiers.

SGKs are not only another money making venture for data sellers, they also enable threat actors to collect relational data to perpetuate other types of fraud. Searching for a phone number in an SGK may return other sensitive information, like related account IDs or email addresses. Actors can use this type of information to support phishing campaigns, social engineering, and identity theft.

Summary of the Chinese threat actor landscape

While this booming illicit data trade originates in Chinese-language communities, the activity from these threat actor groups can and does impact people worldwide. With an emphasis on real time data, Chinese cybercriminals are relentlessly working to make PII persistently available to other actors to conduct cyberattacks.

Key takeaways

- The threat extends beyond China’s borders: Anyone with a Chinese SIM that connects to a Chinese telecommunications provider is vulnerable to this criminal activity, as well as anyone who has downloaded an app with a malicious SDK. The use of secondhand data and penetration services also extends the threat.

- The illicit data trade occurs beyond Telegram: While our research honed in on Telegram- and X-based actors and breaches, the Chinese illicit data trade extends to both clearnet and Tor-based forums and markets.

- No known connections to Advanced Persistent Threat (APTs): When people hear about Chinese cybercrime, the assumption generally tends to be that a state-sponsored group is involved. However, there are no overt indications that these Telegram-based actors are affiliated with APT or nation-state cyber actor groups. Additionally, the primary motivation of these Telegram actors appears to be financial, as opposed to espionage.

- Strong emphasis on real-time data: Perhaps the most material difference between the Chinese illicit data trade and the Western data leak market is the emphasis on real time data. It exhibits that these actors have consistent access to seemingly vast amounts of sensitive data.

The SpyCloud Labs research team actively monitors the Chinese threat actor community for insight into trends and TTPs, and will continue to do so. For more information from our team, watch this recap of our analysis on the current Chinese threat actor landscape.

See us live: SpyCloud Labs researchers will present a more in depth assessment of the Chinese threat actor illicit data trade ecosystem in April at Disruption24.

Uncover more of the latest security research from SpyCloud Labs.

[1] hxxp://epaper[.]zqrb[.]cn/html/2022-01/20/content_802637[.]htm

[2] hxxps://yon888[.]com/jjxw/7176[.]html

[3] hxxps://www[.]gizchina[.]com/2019/10/11/2g-phones-still-sell-more-than-5g-devices-in-china/