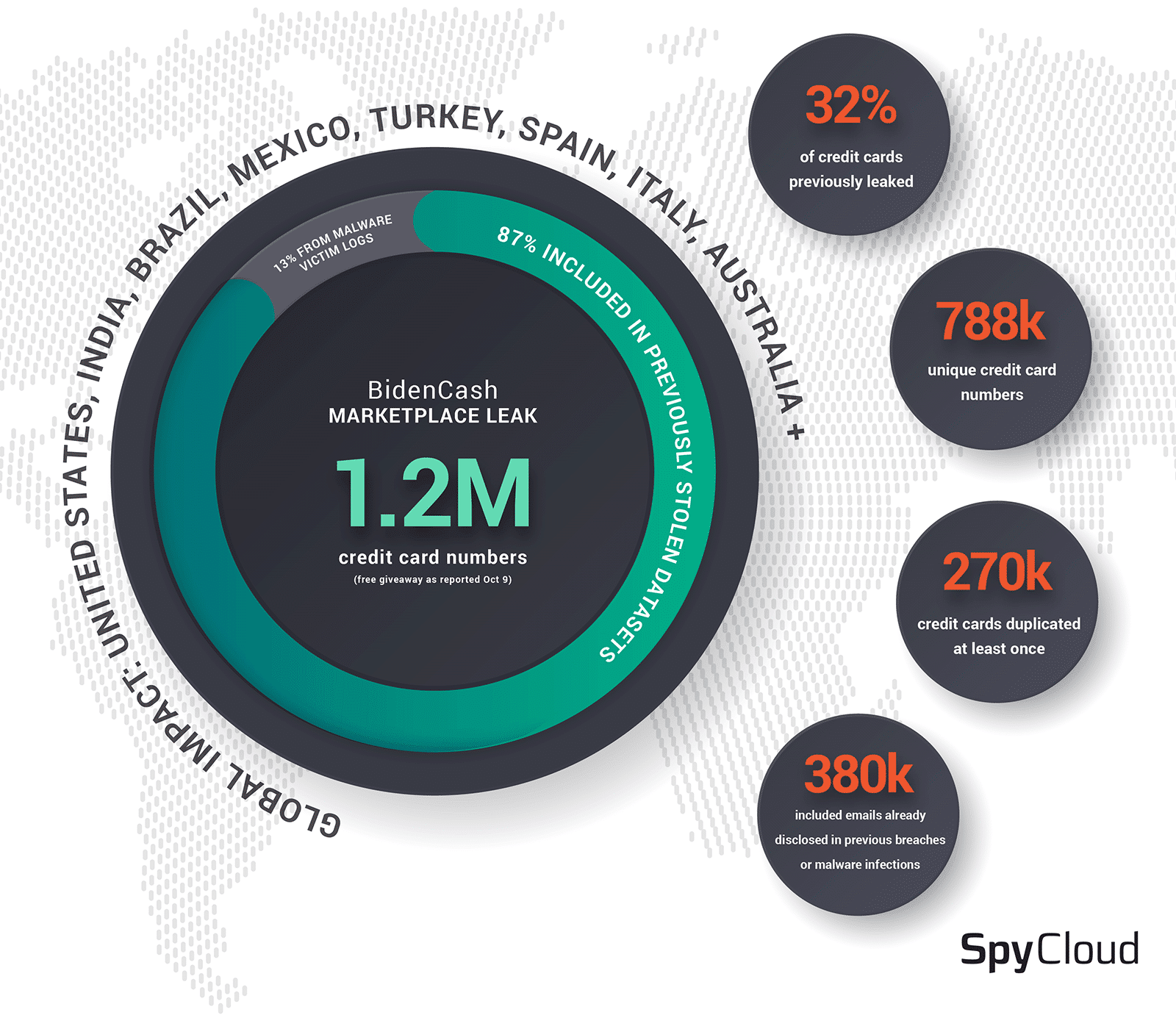

On Sunday, underground carding marketplace BidenCash made available for free download a file which purported to contain approximately 1.2 million credit cards. According to BleepingComputer, BidenCash is a new entrance to the dark web carding space, having launched as recently as June 2022 with an initial – and smaller – dump of stolen credit cards in an apparent attempt to attract business. According to analysts at D3Lab, who were contacted by BleepingComputer for comment, roughly 50% of the Italian cards found within the dump had already been blocked due to the issuing bank’s discovery of fraudulent activity, as of Oct 9th.

Researchers at SpyCloud conducted an analysis of the BidenCash dump by comparing the information – namely, credit card numbers, email addresses, and phone numbers – against the SpyCloud datalake of approximately 280 billion recaptured breach and malware records, in an attempt to determine potential sources of the information and confirm the authenticity of the records contained therein.

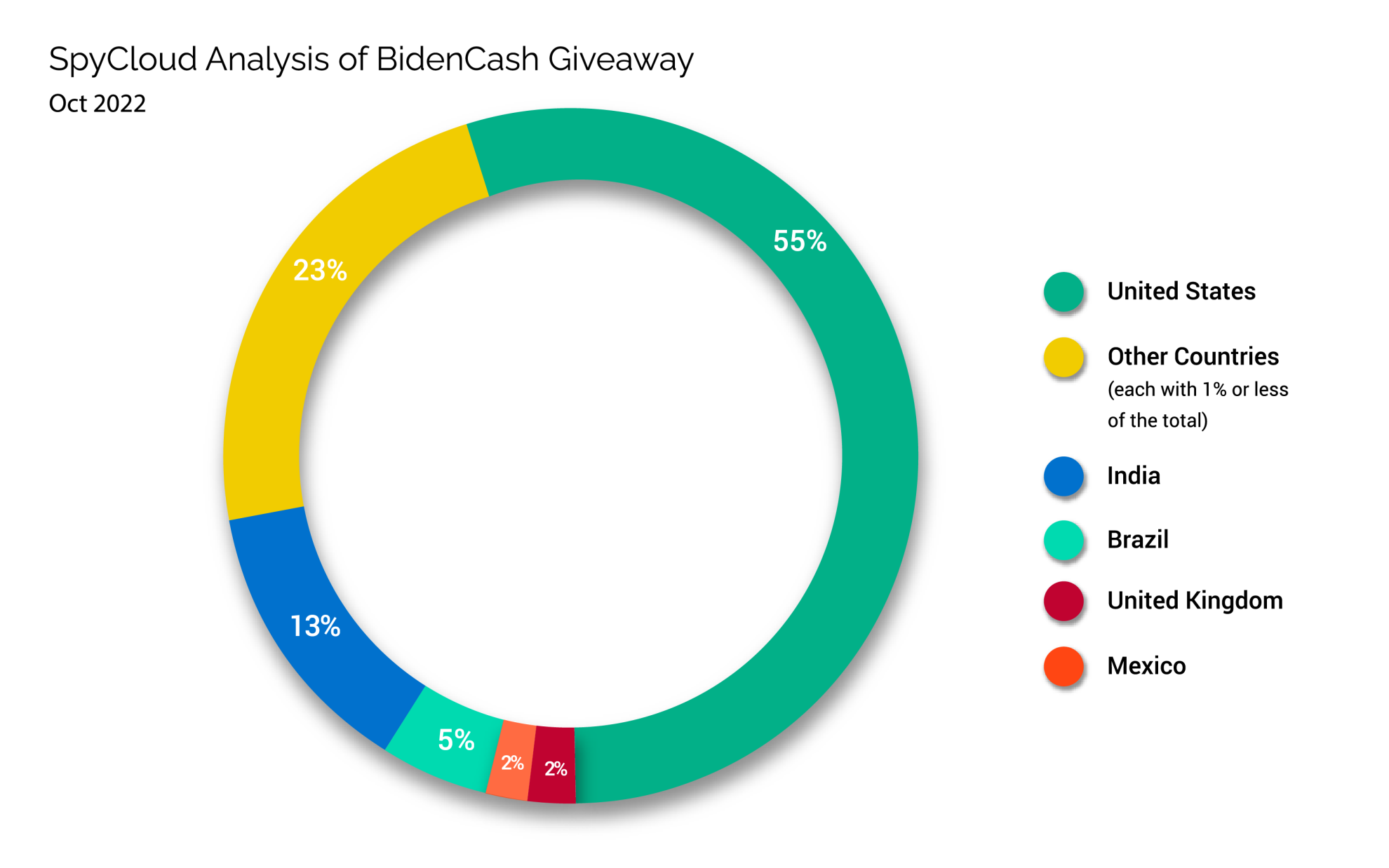

While most of the records contained an address in the US, a significant number of victims resided in countries including India, Brazil, and the United Kingdom:

Examining records by country, and excluding countries with less than 1,500 victims – as defined by the inclusion of a country-specific address within the victim’s record – data fidelity varied widely. For example, while 148,239 records from victims residing within India were found in the data, less than 1% of those records contained either a date of birth, email address, or social security number.[1]

By contrast, approximately 40% of the 15,122 records with an address in Turkey contained a date of birth, which was substantially larger than the next largest representative country, Germany, with only 5.3% of records containing a date of birth. Only 1.2% of records with a US address contained a date of birth, with less than 1% having an associated social security number.

Duplication of records was also a consistent finding. 82,498 credit card numbers were repeated three times, 195,853 were repeated twice, and 509,882 were not repeated within the dataset. All together, only 788,233 unique credit card numbers (68.6% of the records we were able to extract from the source data) existed within the BidenCash dump.

While this duplication is not surprising, given the data was likely compiled from many different sources, it does call into question the top-line number advertised by BidenCash.

Next, we turned our analysis to determining the source of the data. Using SpyCloud’s data repository and the different records contained within the BidenCash dump, 139,619 credit card numbers were found within an existing breach or malware infection. While the majority of the credit cards were disclosed in public breaches or sold online in dark web forums and on marketplaces, a portion – approximately 13% – were found in botnet data derived from information stealer infections. While data from several named stealers were found within the subset linked to these sources, the majority of the data were derived from logs created by the RedLine and Raccoon information stealers, both of which are sold online as malware-as-a-service, which enable cyber criminals to deploy ready-made malware against victims with the express intent of stealing sensitive information, such as financial data.

The earliest credit card number was observed by SpyCloud on January 9, 2020, and the most recent record was identified on October 6, 2022. Numbers from malware logs were even older, with some having originally been stolen in April 2018. Expressed longitudinally, the majority of the credit cards were leaked between July and August of 2021, with smaller exposures occurring between April and May of 2022. Taken holistically, and based on the data for which SpyCloud has visibility, the majority of the credit card numbers were identified from breaches and in malware logs 6-14 months prior to their inclusion in the BidenCash dump.

Ancillary record information, including phone numbers and email addresses, were also not unique to the BidenCash dump.

Of the 380,405 records for which an email address was included, approximately half were previously identified by SpyCloud as having been disclosed in a public breach or malware infection.

This finding was consistent for the 578,524 phone numbers found in the data, of which 242,556 phone numbers had previously been seen by SpyCloud. Observation dates of phone numbers and email addresses were much broader than credit card information, with the first records having been observed as far back as 2017 and the most recent records observed the week before the dump was posted.

Notably, while significant overlap existed between credit card numbers identified in public breaches, the additional records existed for email addresses which did not correspond to the credit cards listed in the breach. This suggests additional credit card information may exist within the source data used by BidenCash to compile the public dump but which was excluded. This data may have been held back for later sale or could have been unavailable to the individual(s) who produced the dump due to the method by which it was acquired.

Conclusion:

Based on the analysis by SpyCloud, it is likely that the data released by BidenCash is a compilation of information which largely existed in some format prior to its disclosure by the carding marketplace. While a portion of the data originated from botnet logs and thus may be of higher value to the criminal, the bulk of the records were derived from limited breach records and should be easily negated by processes likely already underway – if not already completed – by banks and card issuing organizations. While a novel marketing method, it is unlikely that the disclosure of these credit card numbers alone will significantly impact the criminal market for stolen financial data.

Nonetheless, the disclosure of records contained within the dump, and especially less mutable records like phone numbers (508,000), social security numbers (10,000), dates of birth (18,000), and physical addresses (847,000) may pose a significant concern to affected individuals. Armed with data about a person’s life, even if it’s not validated for accuracy or current legitimacy, fraudsters can attempt substantially more inventive ways to impact individuals’ financial lives and disrupt the enterprises they do business with in the creation of synthetic identities, for example – situations that can be considerably longer-lasting than a one-time disclosure of a credit card number. Social security numbers are not easily changed, and defending against future identity theft and collateral financial fraud can be a long-term battle for individuals and businesses trying to validate transactions with users whose information has been disclosed in this way.